比丘近巖 2012年3月14日星期三 於萬佛城 The article written by Bhikshu Jin Yan on March 14 (Wednesday), 2012 at CTTB

I. 引子

1) 雲門三句:「我有三句話,示汝諸人。一句涵蓋乾坤,

2) 雲門祖風:「忘餐待問,立雪求知,困風亡時於十七年間,涉南北數千裏外。」——文偃禪師致南漢王劉晟之《遺表》(節錄)

雲門先賢們繼承這種精神,

******************************

II. 禪一在大覺

雲門,對我來說並不是一個陌生的名字。

只是隱約記得——它,在廣東乳源,因參方而“被”

今年一月,從香港靈會山慈興寺打完三個星期禪七的我,

我想可能是因為我在慈興寺打七期間,

一月五日到深圳,六日抵廣州,七日就高速公路北上﹝

午齋之後,我們匆匆趕路,三四點鐘,終於到了雲門。

這些沙彌們,在晚上的禪堂就與我坐鄰單;

打完那天晚上的七,大和尚提早放香,讓大眾早點回去休息。

一方面我回廈門的歸心似箭,另一方面陪我來的居士們也無心眷留—

******************************

III 典型在夙昔

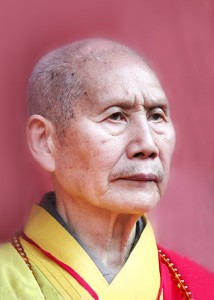

平時對佛源老和尚知之甚少,

平時對佛源老和尚知之甚少,

我對大覺寺的好感,大概是因為佛源老和尚的緣故,

一)疾風知勁燭,烈火見真金

從虛老年譜中,1951雲門事變突發,

在那時的一波波的政治運動中, 虛雲老和尚是首當其衝的;有人昧著良心羅織虛老的罪名,

二)十方翹首宗風振,第一功勞在樹人

上個世級八十年代,佛教界面臨百廢待興的時候,佛老事必躬親,

一、 三不

(1)、不住城市∶

「在大城市許多時候都是人山人海,

(2)、不住小廟∶

老和尚有一次在禪七解七前開示說,「解七後,

(3)、不住經懺門庭

為了賺錢而不惜濫做經懺的寺廟,佛門稱之為經懺門庭。

「解放前在杭州,做一次經懺就發財囉。當時做經懺,

二)、三要

(1)、要將身心傾注在祖師道場

因為祖師道場多為名山叢林,「為宏道利生之法窟,

(2)、要把禪風發揚光大

「要好好用功,不要偷懶!一心一意把書讀好,規矩法則學好。

(3)、要把明心見性作為終身奮鬥的目標

有人就問,為何古人見性多而今人見性少及參禪要訣請益,

Starting from the Three Phrases of Yunmen

I. Preface

Yunmen said, “I have three phrases to reveal to you: ‘to contain Heaven and Earth,’ ‘to sever the many streams,’ and ‘to drift with the waves.’ If you can discern and understand these three, then you are ready to study. If not, then you are still traveling arduously along the road from Changan.”#—from The Five Lamp Compendium

The Tradition of Yunmen: “Waiting to inquire, I neglected to eat; seeking understanding, I settled in the snow; stranded in the wind, I lost the time. For seventeen years, my footsteps traced a thousand miles, north and south across the rivers.” — Master Wen Yan, A Bequeathed Report to the King Liu Sheng of Southern Han.

The worthy patriarchs of the Yunmen School carried on the spirit of Master Wen Yan, laying a solid foundation for the Yunmen School, which flourished in China for over two hundred years. It is no wonder that there was a saying at the time: “Yunmen is the emporer; Linji is the general; Caodong is the scholar.”

******************************

II. A One-Day Chan Session in Yunmen

The name Yunmen, or “Gate of the Clouds,” was not at all unfamiliar to me. I had only a vague memory of the place — Located in Guangdong Province, it used to be the headquarters of the Yunmen Lineage, whose founder, Dhyana Master Wen Yan (864-949) had spread his teachings widely. I remembered that it was the place where the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua had bid his last farewell to the Elder Master Hsu Yun, where, in 1951 and 1952, Venerable Master Hsu Yun and other monks had undergone great ordeals of suffering, ordeals which history would later remember as the “Yunmen Incidence.”

The name Yunmen, or “Gate of the Clouds,” was not at all unfamiliar to me. I had only a vague memory of the place — Located in Guangdong Province, it used to be the headquarters of the Yunmen Lineage, whose founder, Dhyana Master Wen Yan (864-949) had spread his teachings widely. I remembered that it was the place where the Venerable Master Hsuan Hua had bid his last farewell to the Elder Master Hsu Yun, where, in 1951 and 1952, Venerable Master Hsu Yun and other monks had undergone great ordeals of suffering, ordeals which history would later remember as the “Yunmen Incidence.”

In January 2012, after having completed three weeks of Chan Session in Cixing Monastery on Linghui Mountain of Hong Kong, I made my way northwards to Xiamen to see my parents. I had no plan or intention to go to Yunmen; I don’t know if it was the will of Heaven, or a mere coincidence, that my path was diverted from Shenzhen to Guangzhou, from Guangzhou to Qujiang of Shaoguan, and then to Yunmen. In Qujiang and Yunmen I had an opportunity that I had been longing for, to visit and pay reverence to two of the important Chan Monasteries in China, both of which have a history of over a thousand years: the Sixth Patriach’s Nanhua, or “Southern Flower” Monastery, and the Dajue, or “Great Awakening” Monastery of Yunmen.

This opportunity was possibly due to my readings of Dhyana Patriarch Wen Yan’s stories and teachings. During the Chan Session in Cixing Monastery, I read books by Venerable Master Hsu Yun and Venerable Master Sheng Yi. At the evening discussion with the participants, I quoted from the stories that I read about Master Wen Yan and his biography. I did not forsee that I would embark upon a journey to Yunmen several days later. Long before this, after reading Venerable Master Hsu Yun’s Chan instructions and biography, the word “Yunmen” had left a deep impression upon my memory. Nevertheless, I did not notice that the famous Chan instructions given in Shanghai by Venerable Master Hsu Yun had been compiled by Master Fo Yuan, whose name means “Source of the Buddha.” I also had not noticed the fact that in the past half a century, Yunmen had been closely associated with the name of this eminent monk, the late Venerable Master Fo Yuan.

I arrived in Shenzhen on the 5th of January, and Guangzhou on the 6th. By the next day I was on the highway, traveling north to Yunmen. I encountered many tollgates on this highway; Every so often, I would find myself coming to a new tollgate. The charges were high, not two or three yuan (China’s currency), but hundreds (at one time 105 yuan). It was quite shocking for me to see charges so high.

When we passed by Nanhua Monastery, we had lunch at the Vegetarian Restaurant. Because our destination was Yunmen, we had not informed the guest department at Nanhua Monastery that we were coming. During our short stay at Nanhua Monastery, we never saw the resident monks there.

After lunch, we went to pay our respects to and worship the remains of the Sixth Patriarch Master Huineng, Master Hanshan (of the Ming Dynasty), and Master Dantian. We also paid a visit to the Sash Rinsing Fountain, and the layman Chen Yaxian, who was the previous owner of the property at Nanhua Monastery.

Afterwards we left for Yunmen, arriving at Dajue Monastery at about three or four o’clock. Dajue Monastery rests on Guanyin Mountain, where the ancient trees still reach upwards to the sky. Long and slender bamboo also towered above us. Across from Dajue Monastery was the Yunmen Buddhist Academy. As we made our way up the mountain paths, bamboo rose up on both sides, as if to welcome and greet these guests.

Afterwards we left for Yunmen, arriving at Dajue Monastery at about three or four o’clock. Dajue Monastery rests on Guanyin Mountain, where the ancient trees still reach upwards to the sky. Long and slender bamboo also towered above us. Across from Dajue Monastery was the Yunmen Buddhist Academy. As we made our way up the mountain paths, bamboo rose up on both sides, as if to welcome and greet these guests.

High up and to the left, we could see the remedial construction project to repair the sharira tower of Master Fo Yuan.

After paying reverence to the Sharira tower, we went to report to the Guest Department of Yunmen. It was 5:30 PM, and an audience with the abbot, Dharma Master Ming Xiang, had already been arranged for us. He had returned in haste to the monastery after having attended some end-of-the-year meetings in various places. The abbot and other key-positioned monks were busy preparing for the twentieth anniversary of the founding of Yunmen Buddhist Academy.

On our way to meet with the abbot Ming Xiang, I saw that a group of more than twenty young novices, ranging in age from about 10 to 16, were walking single file to the Dining Hall to have their meal. This dinner is called a “medicine meal” in monastic terminology. The wholesome demeanor and the orderly serenity of the group, together with their simple attire and energetic manner, were quite scenic, and became a highlight of my visit. If properly educated, I believe they will definitely become pillars for a future Buddhism. Seeing them, I have a sense of hope for Buddhism in the future.

These young novices were also attending the Chan Session. Some were sitting near me, or right next to me. It was Saturday, the last day of the fifth week of the Chan Session, so the abbot came to give a special instruction on Chan practice. A few other important monks, those who held key positions in the monastery, also took turns giving instructions that night.

The Chan Hall at Dajue Monastery was a large and versatile multi-purpose hall. When Chan sessions were not taking place, it could be used as an auditorium, and during the Chan Session, it could be quickly converted to a Chan hall.

Among the participants present were quite a few college students. When the whole assembly was participating in the Chan session together, the energy and feeling was very inspiring. It moved me to consider coming to some of their Chan sessions in the future. I had rarely seen such large Chan monasteries in China, with so many sincerely practicing monks. Much of this success can be attributed to Elder Fo Yuan, who put in many decades of effort. At one time in the past, there were only three monks at Yunmen. They chose to stay on despite the very harsh political climate. The temple facilities and buildings had been destroyed. Elder Fo Yuan overcame these difficulties and inspired the monks and lay people to rebuild the monastery gradually. Before passing away, he asked the monks to carry him to the Chan Hall, where he took the traditional leave of absence from the Sangha, and gave his last blessings to the Chan students.

After the sit, the abbot announced that people could go back to the dorms and rest early. Perhaps this was because it was the fifth week of Chan and people were worn out. Sitting Chan can be like a kind of protracted warfare. What is a dauntingly long session for beginners is no problem for seasoned cultivators. I could sense from the novices sitting near me how they felt about the Chan Session.

A novice about the age of 15 or 16 was barely making it. He was crouched over, his posture bent, waiting for each second to pass quickly. He would try to whisper to his fellow novices whenever the monitors were not present. Afterwards I asked another bhikshu if they had created a different schedule for the young novices. He said the schedule was the same for everybody. I sighed, reflecting to myself that it would be wiser to tailor a schedule that met the novice’s experience and needs.

I could not wait to go back to Xiamen to see my parents, and the lay people who accompanied me were eager to go back to Guangzhou. So on the 8th of January, we drove south, with a feeling of sadness at parting from Yunmen. This put an end to our day of study at Yunmen.

阿彌陀佛